The passing of federal-level anti-gay legislation in Russia has been the source of much recent attention. The law criminalizes positive portrayals of gay people in the name of the children. For the Russian government, this represents the latest in a series of policies aimed at oppressing queers.

This bill is terrible and there has rightly been much attention devoted here on that matter. However, I think that there needs to be a critical look at why this issue gained such prescience in the media. Especially since I’ve come to believe that the causes behind this outcry are also what drives the silence against the treatment of queers in states like Iraq, where they can be executed.

So let’s start with the fact that human rights are wielded by Western governments as political tools. It’s a way to get public support and amplify our power through intermediaries like the United Nations.

Now I’m sure that there is some genuine concern by politicians. However, it is no coincidence that human rights are brought up exclusively against states that don’t bow to our interests. We will publicly denounce Iran for their human rights record yet Saudi Arabia, where treatment is much worse, will at most get a chat behind closed doors.

When it comes to Russia, tensions have been on a high with the West. More acutely, the Russians did not hand over Edward Snowden at the request of the United-States. Cue this atrocious bill in a country sensitive about its image ahead of the Sochi Olympics, and cue a means to get back at Russia for not doing what the US wanted.

There’s a word for feigning interest in queer rights to exert power. It’s called homonationalism. While it worked in the favour of human rights in this one instance, it is also what sustains oppression through strategic silence in nations that do cater to our interests.

Governments are no less psychopathic than corporations when it comes to treating people and their well-being as commodities.

So that’s the government. What about the people? Because this outcry did get lots of ground-up attention. That’s great. What’s not great is that we just have to wait a few months and all those people attending rallies today will have close to zero interest in this issue.

That highlights the second problem around popular culture and causes. Mainly that it is not aware of situations, but rather changes to situations, and only then for a brief moment. After that, it gets incensed by the next thing.

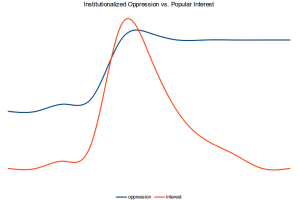

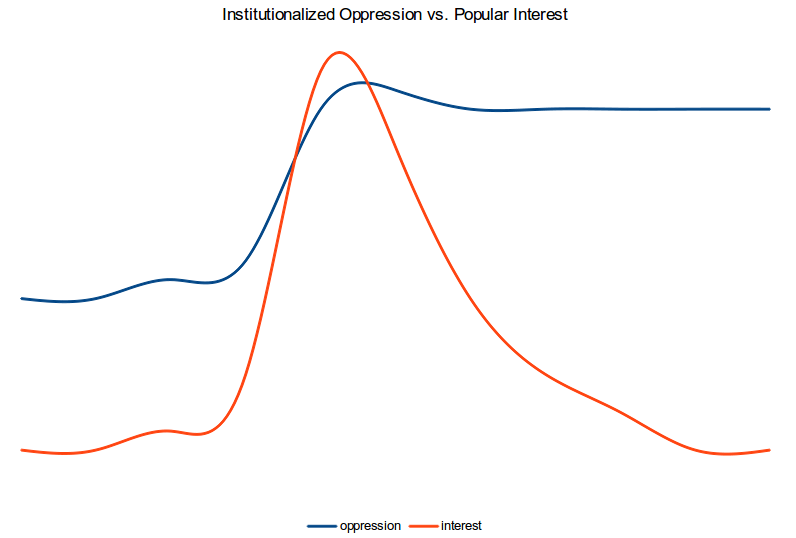

I suspect that it might be because there’s a certain gratification that comes from being angry at new things. There’s a social element too. Keeping tabs on existing things meanwhile takes work and is boring. Here’s a completely unscientific chart because I like charts.

The last thing on people’s radar for queer rights was Uganda. How many people care about Uganda now? How many people even know what is going on? There’s no coverage, no more likes on Facebook or reblogs on Tumblr. It got boring.

This kind of way to look at the world makes us completely oblivious to situations that are more dire. There’s no awareness of things even at home. So we become silent about all the places where atrocities are committed, only speaking out when there’s a flurry of Internet activity about somewhere new.

Human rights are a long term thing, and this formula isn’t how we’re going to get there. We can do better than this.

It starts with holding our government accountable when it is silent about human rights violations among its allies. There is a cost to doing this – the UK at one point spoke about concerns around losing precious counter-terrorism arrangements with Arab allies. This isn’t a black and white decision, but it’s nonetheless the right decision.

“Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

– Elie Wiesel

As for the problem of slacktivism, which is what you can call this social-network instigated model of very ineffective advocacy, it’s a bit of a harder issue to solve. Advocacy groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch do a good job of keeping global tabs, though both are subject to bias of the “popular” causes of slacktivists for the sake of securing donations.

But going back to individuals, you’re competing against the instant gratification afforded by social media. Maybe it’s erroneous to believe that every slacktivist could be an effective advocate.

Perhaps the solution is then not to turn them into one, but capture their short-lived bouts of interest to expose them to awareness materials to make them more empathetic as a whole. Give them the skills to be better people in those moments when they’re receptive. Maybe insert some hints as to how the home situation isn’t nearly as good as they’re led to believe it is, and leave the advocacy work to traditional groups.